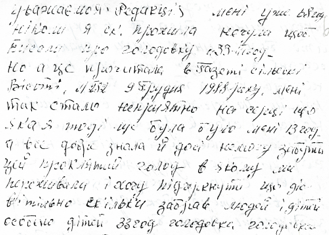

Full Name in Ukrainian: Дука Анастасія Іванівна

Full Name in English: Anastasiia Duka

Data of Birth: 1920

Place of Birth: Ustymіvka

Raion: Krasnohrad raion

Oblast: Kharkiv oblast

Country: Ukraine

Copy of original: Yes

Envelope: Yes

Number of pages: 8

Keywords: Ukraine--History--Famine, 1932-1933--Personal narratives; Famines--Ukraine--History--Sources; Famine victims; Holodomor; Голодомор; child; survival strategies; food substitution; cannibalism; cow; barter; compassion; search brigades; perpetrators; disappearance; robbery.

Notes: Abridged letter is published in 33: holod. Narodna Knyha-Memorial book, Kyiv: Radiansky pysmennyk, 1991, p. 491.

Anastasiia Duka was 13 in 1933.

Anastasiia writes about surviving the Holodomor in her native village of Ustymіvka (which she calls Ustynovka), Krasnohrad raion, Kharkiv oblast (Ustymivka, Zachepylivka raion, Kharkiv oblast in 1988).

Anastasiia was one of five children in a family which she describes as hard-working. They had a cow and a heifer, grain, corn, a chest of flour, salted cheese and salo (pig’s lard), and potatoes in their cellar, when a search brigade came searching for food in their house. One of the search brigade activists showed some mercy on them and pretended that he did not see some food supplies in the attic. Everything else, including the heifer, was taken away by the activists.

Anastasiia’s father decided to kill the cow, before it is taken away, and sell the meat to buy grain. He sold the meat but, on his way home, he was robbed of the money he made. The robbers also beat him and threw him in the river. He made it home only in the morning and cried at home over the loss of the cow and the money. Shortly after he arrived home, the head of the collective farm Kukharenko and the head of the village council came to the house and took Anastasiia’s father away. Anastasiia never saw him again and never found out what happened to him. Her mother tried to inquire about his fate at the time and went to the oblast centre, Kharkiv. She did not learn anything. Anastasiia writes that Kukharenko is still alive, and that she cries and asks him about the fate of her father every time she sees him, but never gets an answer.

Anastasiia’s mother with two daughters were working in the beet fields to survive. Their main food was beet leaves that they gathered in the field, cut and boiled. The next spring (presumably in 1934), only the bosses had something growing in their gardens because the rank-and-file villagers had no seeds to plant and no implements to cultivate the land. A bucket of potatoes cost 500 rubles, a glass of grain cost 300 rubles, and a glass of beans cost 100 rubles.

The family was starving, so Anastasiia’s mother told her to take her seven-year-old brother to the railway station and leave him there. (This is what many people did at the time in the hope that the child would be placed in an orphanage and have better chances of survival). Anastasiia could not leave her brother and brought him back home.

Anastasia mentions neighbors who were desperate enough to eat the meat of their dead children and explains that without bread she could never feel full. She cannot understand why the famine was allowed to happen and why no one helped the starving. It seems normal to her that people from all over the world help each other in case of a natural disaster. While children in the Soviet Union were well cared for and mothers were given maternity leave at the time she was writing the letter, too many children had died of starvation during the Famine.

SYNOPSIS

The UCRDC depends on voluntary donations – both individual and institutional - for its financing.

It provides receipts for tax purposes.

-

‣Home