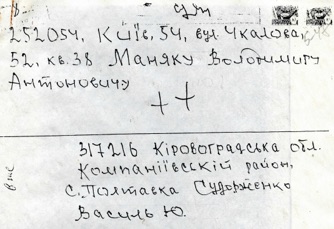

Full Name in Ukrainian: Василь Судорженко

Full Name in English: Vasyl Sudorzhenko

Data of Birth: Unknown

Place of Birth: Poltavka

Raion: Kompaniivka (currently Kropyvnytsky raion)

Oblast: Odesa oblast (currently Kirovohrad oblast)

Country: Ukraine

Copy of original: Yes

Envelope: Yes

Number of pages: 21

Keywords: Ukraine--History--Famine, 1932-1933--Personal narratives; Famines--Ukraine--History--Sources; Famine victims; Holodomor; Голодомор; collector of witness accounts; search brigades; family mortality; perpetrators; activists; food substitution; survival strategies; theft; poverty; school; child; childhood; ration in school; trauma; burial; horses; cows.

Notes: This letter is composed of witness accounts recorded by the author.

SYNOPSIS

The UCRDC depends on voluntary donations – both individual and institutional - for its financing.

It provides receipts for tax purposes.

-

‣Home

Vasyl Sudorzhenko collected several memoirs about surviving the Holodomor from the residents of the village of Poltavka in Kompaniivka raion, Odesa oblast (currently Poltavka, Kropyvnytsky raion, Kirovohrad oblast). He estimates that at that time, close to 80 people died in the village at the time. His interviewees are Tetiana Oleksiivna Papusha, Zubko family, Maria Nikiforivna Zaremba, Yavdokha Kolos, and Prokip Isakovych Liubar.

Tetiana Papusha (b. 1918) recalls how their family was collecting leftover wheat spikelets in an already harvested field in order to deliver the 10 kilograms of grain that the search brigade demanded they deliver overnight. (According to Wiki, Tetiana’s father, Oleksii Papusha was the first head of the first collective farm in the village).

Zubko family members died one-by-one, starting with the youngest boys Stepanchyk and Yashka. Oliana, the eldest of the children, spent her days in the fields trying to collect a bucket of potatoes for the family. After her brothers’ death, Oliana gradually declined too, unable to leave the house. The teacher in the local school left the school abandoning the students. The students who used to count on hot breakfasts at school started dying one-by-one. Eventually, Oliana’s parents Svyryd and Hanna died too.

Maria Nikoforivna Zaremba (b.1920) recalls that their family moved to Poltavka in 1924 and lived very poorly, but eventually bought a cow and a horse (that they used together with Papash family). Her anecdotal recollections about armed “activists” dressed in leather jackets and their activities in the village include: a story about activists escorting somebody they arrested and “painting crosses on his back”, a woman-activist called “a python in pants,” likely for her fervor in performing her duties, and a kulak (kurkul) Shpylka who was deported to Siberia. The activists took away the Zarembas’ horse. Horses were not fed in the collective farm. Skinny and exhausted, roaring horses were put down and dragged to an animal graveyard behind the village. Zaremba’s mother took some horse meat from that graveyard, boiled and fed it to the youngest in the family, three and five-year-old boys. The boys died. The remaining six family members ate a watery broth of three spoons of soy. Zaremba’s mother’s body began swelling after she ate that broth and she soon died.

The thought that she did not save her brothers, haunted Maria Zaremba for the rest of her life. She cannot comprehend why people were starving to death, begging for food, dying on the streets, their corpses laying by fences for weeks, while there were piles of grain and corn at the local threshing ground and in Sinokosivska church.

Zaremba also recalls how the number of students in school was decreasing with each day. More than forty children died of cold and starvation. They were taken to the village cemetery wrapped in cloth.

Yavdokha Kolos (b. 1925) describes the last moments of her father’s Trokhym Kolos’ passing away of starvation with his wife, Maria Kolos, by his side. Maria and her two sons, 12 and 13, also died of starvation in 1933.

Prokip Liubar’s family of six was very poor. His parents were sick. They lived in a dugout and wore worn out clothes given to them by other people in exchange for looking after their cows and horses.

In 1933, “activists” took from them three buckets of rye, a bucket of beets, and whatever potatoes they could find in the cellar. Liubar’s father protested, the children were crying, and the activists’ only reply was that they had a quota to fulfill. The family survived on horse meat stolen from the graveyard for dead livestock, ate their own dogs and even gophers. At some point they discussed going to other villages and begging for food but decided against it. In the spring (of 1933) Prokip and his brother decided to try and steal the grain taken from the nearby villages and stored in Sinokosivska church located 7 km away. Although a guard was always posted at the church, they found a way to break a window on the side of the church and collect the grain that poured out of the window into a sack. They believed that it was not theft as they were taking back what had been taken away from them. They also raided “kulkuls (kulaks) and activists” and sneak into an open-air threshing floor. This saved their family.